The world’s space agencies are calling for a new generation of satellites that would be precise enough to map greenhouse gas emissions from individual nations. Their goal is to replace decades of rough estimates with advanced monitoring of what has become one of the world’s foremost concerns.

The plan, based on a growing body of research in space sensors, is delicate politically because the global system could verify or cast doubt on emission reports from the 196 member states of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, which was adopted in 1992. If built, the system could serve as an independent way to measure greenhouse gases and encourage lax countries to better comply with abatement goals.

The recent Paris accord, which calls for the “verification and certification of emission reductions,” essentially gave the plan a diplomatic stamp of approval.

The proposed system of satellites, six to eight in all, would be in orbit by 2030 to map clouds of carbon dioxide, the invisible gas linked to climate change. Rough estimates put the system’s cost around $5 billion. It would resemble the global fleet of weather satellites that observe water clouds.

Officials call the undertaking crucial for better dealing with aspects of climate change linked to civilization’s waste gases.

“It’s what we have to do if planet Earth is to be saved,” said Jean-Yves Le Gall, the head of France’s space agency and a leader of the initiative. “It’s a consciousness shared by the heads of all the space agencies.”

It’s well known that carbon dioxide emissions from natural sources and fossil-fuel combustion merge slowly into a global average long reported to be rising. But the exact contributions of individual countries are something of a mystery.

Each nation draws on a mix of surface readings, economic analyses and ecological estimates to quantify their emissions. Experts say the self-reporting varies enormously in thoroughness, frequency and accuracy.

The 1992 climate accord calls on industrial states to issue reports annually, typically with much documentation. But developing countries, which comprise the vast majority of the pact’s signatories, are required to make only sporadic communications. For instance, the world’s biggest emitter, China, issued reports in 2004 and 2012.

The sense of urgency behind the satellite plan arises in part because developing countries a decade ago surpassed industrial nations as global emitters of carbon dioxide from fossil-fuel combustion. Their estimated share stands at 60 percent.

Climate experts say the rising percentage of sketchy information makes the overall portrait of global emitters increasingly blurry.

“The uncertainty,” an October study by the European Commission said, “has increased up to the point where it could undermine the credibility and the stability of future climate agreements.”

Starting last fall, space agency leaders from China, India and other developing countries and industrial powers, including the United States, seized on such analyses to begin arguing for the satellite fleet. Last month, at a meeting in New Delhi, they issued a draft public declaration.

“An international independent way of estimating emission changes,” it said, “would create a level playing field.”

On Monday, France’s space agency, known as CNES, for Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales, based in Paris, said it had sent a penultimate draft for approval to the world’s space agencies, 67 in all. The French agency added that it expects a final declaration by Monday.

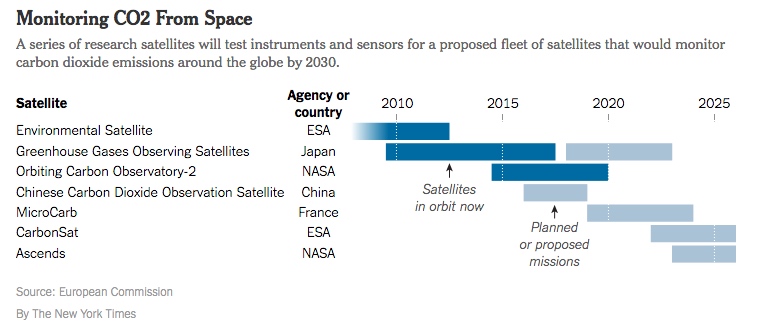

The fleet proposal grows out of strides in the development of carbon-dioxide sensors for use in space. In 2002, the European Space Agency launched an environmental satellite, and in 2014 NASA sent up theOrbiting Carbon Observatory, a satellite that takes readings of the earth’s atmosphere nearly a million times a day.

China, Japan and France plan to launch three more research satellites from now to 2020. Europe and the United States are considering two more.

Experts say that making sufficient progress in the tricky research to warrant the establishment of an operational fleet will pose a major challenge, especially in learning how to distinguish human emissions from natural fluxes.

“This is hard science,” said Stephen W. Pacala, a Princeton University scientist who was the chairman of a National Research Council study on verifying greenhouse gas emissions. “The aspiration is marvelous. But the devil here is very much in the scientific details.”

The fleet, for instance, would have to differentiate new human releases not only from the globe’s existing blanket of carbon dioxide but from such natural sources as volcanoes, forest fires and decomposing plants and animals.

Michael H. Freilich, the director of NASA’s Earth Science Division, said the goal was nonetheless easier in some respects than monitoring the weather from orbiting spacecraft. Clouds and storms are tracked on scales of minutes to hours, he said, whereas the necessary time frame for scrutinizing carbon-dioxide plumes ranges from days to weeks.

The trouble, he added, is that “each measurement you make is going to be harder.”

Dr. Freilich said that he had no doubt that the world’s scientists in coming years would learn how to turn “measurements into information” that could help determine if nations are meeting their reduction goals.

Would such a capability spark global resentment? Could it stir fears of an orbital police force?

“This is exactly what we want to avoid,” Dr. Le Gall of the French space agency said last week in an interview. “It’s a risk. But it’s why we want to have all the space agencies involved” and agreeing on the best way forward.

In 2010, when the National Research Council released “Verifying Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Methods to Support International Climate Agreements,” Dr. Pacala took the opportunity to stress how a new era of precise measurement could have positive implications for diplomacy.

An objective system, he noted, “would give nations confidence that their neighbors are living up to their commitments.”